Fear of Vampires - A Photo Autobiography

My First Communion: Fair Haven, New Jersey; 1966

About this project

As a photo editor and photographer, I spent my working life editing tens of thousands, or possibly closer to hundreds of thousands, of photographs, for sharpness, for technical excellence, for drama, for revelatory information. Using those criteria, very few of the photos I show in this project would make the grade. But to me they have much deeper value, containing as they do the images of people I loved who are now gone, the color, and shape and detail of houses and places, and a record of moments I no longer remember.

When I was a child in the 1960s, in the family and social milieu in which I grew up, appearance was everything. What was not seen was not discussed—for instance death, love, rage, fear, longing—except occasionally in church on Sunday. On the surface, we were polished, spic and span, presentable, conforming, attractive. But inside, in my feelings, as a child, I was often afraid, angry, in turmoil. The confusing discordance of that outer polish and inner turmoil Is what I think this project is about. I wrestle with it still. The vampires of the title arrived about 1967.

To read the photo autobiography chronologically, scroll down to the bottom of this webpage and read the first entry (“A Pigeon-Toed Angel”). Then read the entries going from the bottom of this webpage to the top. I will post new entries at the top of this page as I write them. Please friend me on Facebook if you’d like to see new entries as I add them. English majors, readers and writers out there, if you see a grammatical or spelling error, please drop me a note via by my Contact page—thank you!

**Please scroll to the bottom of this page to read the first entry, then read the entries from the bottom up.

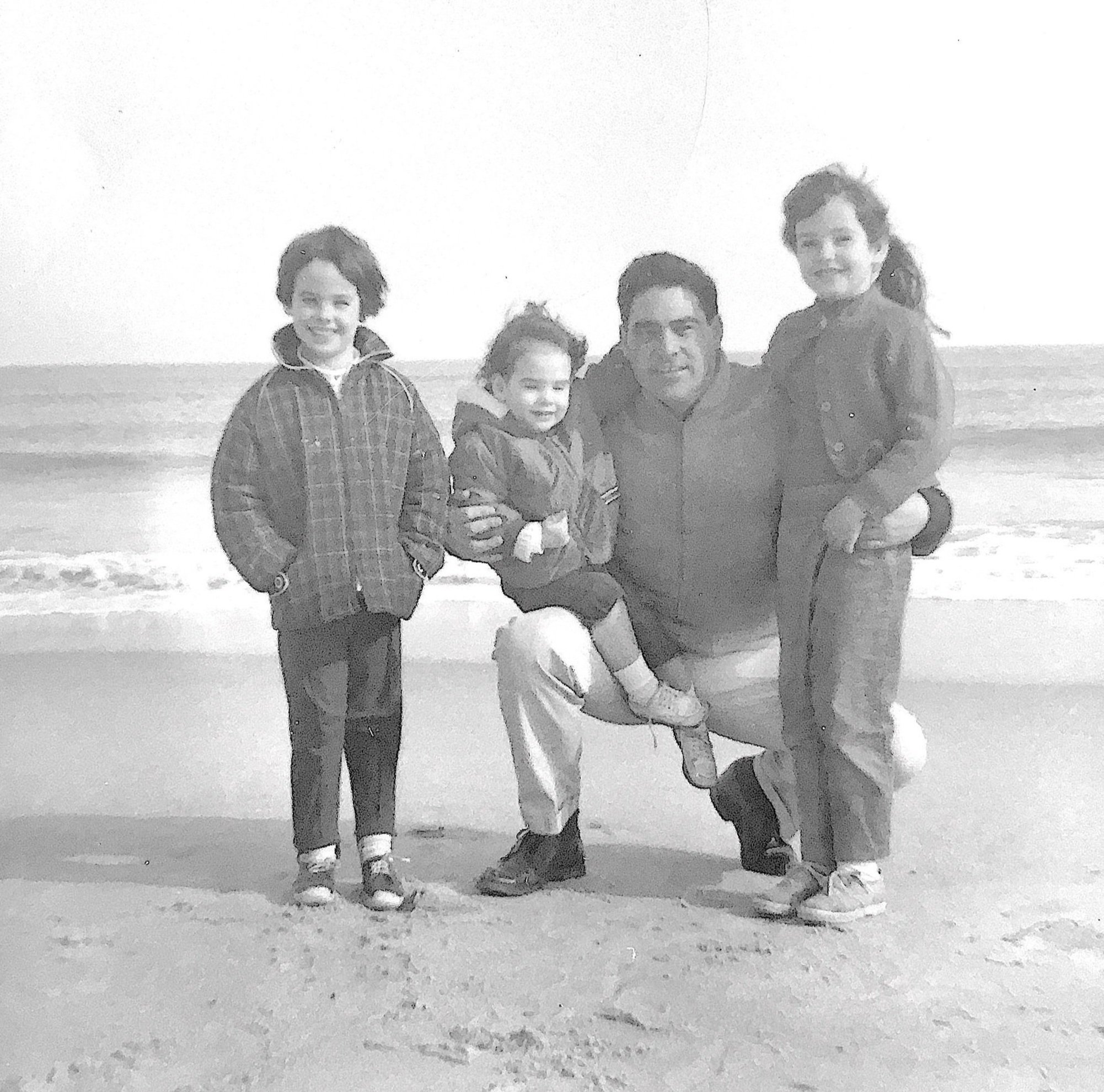

My father holds my youngest and oldest sister at the beach; I am at left; Sea Bright, New Jersey; Winter, 1965

Father

Of all the photos from this period, this one makes me the saddest—because it shows the young, loving father he was—holding my youngest and oldest sister tenderly and protectively—before his feelings were deadened and his rage and nerves out of his control—because of his nightly consumption of gin and tonics, and the hold alcohol took on him.. And I too here (at left) look free, and confident and irrepressibly happy; I was rarely any of those things from age eight on.

One night we were finishing our day as usual at the dinner table, my mother seated at one end, my father, the indisputable lord and master, at the other end, the children along the sides. My father noticed that I had separated my green peas from the rest of my food, and they were sitting abandoned on my plate; I had eaten everything else. I found peas to be utterly revolting, their mushy green interiors, like baby food, and their slimy wrinkly exteriors, like your fingers when you’d been in the bath too long. I can see those disgusting wrinkled peas to this day, like some sort of food aliens would eat. At that tender age of six, my head just above the table, they were just a foot away from my face. “Eat your peas,” demanded my father. All eyes were upon me. I could not. “We are not leaving this table until you eat your peas.” His cruelty became apparent to me. I picked up my fork and pushed it through a pea, and as it came towards my mouth, my throat convulsed in a deep gag from the bottom of my esophagus. A slight moment of panic ensued as it looked like I might throw up on the dinner table. My mother jumped up to clear all the plates, and as she did so, I noticed my father’s plate had a tidy pile of mushrooms shoved to one side. So my beloved father was not only capable of cruelty, but was a hypocrite as well—although I doubt I knew the word then. I was deeply humiliated by the whole incident. I felt enraged by the unfairness and pettiness of his actions, but as I didn’t want to cry, and it was obvious to me that it was pointless to argue with him, I stowed those feelings of rage and humiliation deep in my gut. I had met the enemy, and it was my own father.

First Communion

My First Communion; Fair Haven, New Jersey; May 1966

While we played “strip poker” and developed our obsession with the Beatles, my older sister and I were also studying hard every Sunday in Sunday school to learn by heart the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary ("Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee...Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death, Amen”), The Act of Contrition ("O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee, and I detest all my sins because of Thy just punishment") and other prayers in preparation for our First Communion.

Most confusing for me was that before we could take part in our First Communion, we were first to confess our sins to a priest through a screen in the closet-like confessionals at the back of the church. ("Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. This is my first confession. I have (tell your sins to the priest). For these and any other sins I may have forgotten, I am truly sorry.”) The problem was that no one had told us what was a sin and what wasn’t. I knew there was a list called “The Ten Commandments,” but the nuns and Sunday school teachers had never told us what they were, probably because they did not wish to discuss with us tricky situations like, Commandment Nine: "Thou shall not covet thy neighbor’s wife.” So I remember spending a lot of time trying to find my sins. I let my little sister set the table—was that a sin? I said the word “damn” when my mother wasn’t listening—was that a sin?

The important date finally arrived on a lovely, sunny spring day in May. By that time, I was so worked up by having to walk into the dark confessional to talk to an unknown man through a screen, by pondering my sins and possible punishment for them in purgatory or hell, by contemplating death and “original sin,” and “the body and blood of Christ,” that on entering the church, I ran into the ladies’ room and threw up. My older sister must have been dispatched to coax me out of the bathroom stall to join the line with all the other soon-to-be brides of Christ; my mother would have been busy already seated in the church pew holding my youngest sister Jane.

The ordeal over, I escaped the church out into the beautiful cool spring day and my queazy stomach finally started to settled down, I was handed presents: a white bible with a gold cross embossed on the cover, and a shiny silver rosary with a tiny figure of an almost naked Christ crucified on a silver cross. These were both from my mother’s parents.

With my older sister on the front steps of our house in Fair Haven, New Jersey, spring 1966

Beatles and Barbies

In Fair Haven we discovered the joy of playing long, unsupervised games with our friends and running freely back and forth to each other’s houses. I’m sure our parents would have been surprised to learn that one favorite game we played we called “strip poker.” We loaded ourselves with every piece of clothing we could find, including extra shirts, fishing hats, our fathers' ties, and I remember one clever participant draping wire hangars from her hat. The loser in the simple poker game we played (probably five card draw) had to remove one item of clothing. So many layers of clothing had we that I don’t remember anyone ever getting down even to their underwear, but the possibility and fear of that humiliation kept the game going until we got bored.

I remember regarding Barbie dolls with a certain suspicion—I like to think it was because their huge, disproportionate mountain-shaped breasts and bizarrely flexed, vertical, pointy feet didn’t actually represent anything in the real world. I remember that there was a girl down the street about my age who was wildly enthusiastic about playing Barbies. Her Barbies had a baby, or perhaps it was an imaginary baby, and I remember her with great seriousness teaching me how to make the realistic sound of a Barbie baby crying “WAH-uh-uh-WAH!” Outside we played jump rope and hula hoop and strapped metal roller skates over our shoes. At birthday parties we played pin the tail on the donkey and musical chairs. Non-competitive games hadn’t been invented yet.

My older sister and I had somehow acquired a blue and white plastic record player just in time for the release of “Meet the Beatles!” and we fell ‘in love’ with Paul (my sister) and Ringo (me) as we danced “The Twist” and “The Pony” in our bedroom for hours at a time.

The house my parents bought in Fair Haven, New Jersey, 1965

Suburbia by the Sea

Once my father and mother had recovered somewhat from the debacle of my grandfather firing my father, and my father had realized that running a chain of laundromats was not his destiny, my father was hired once again by the Eastman Kodak Company to work in their New York City office as a sales manager for their microfilm division. My parents found a suburban house in Fair Haven, New Jersey about an hour and a half south of the city by train. There was a pond right down the street where we skated in the winter, and the New Jersey shore with its clean beaches and manageable waves, was just a few miles away. We joined a beach club, which was a huge, multi-story, brown-shingled clubhouse on the beach. Some older children told us there were witches in the attic. My older sister joined the swim team which competed in the club’s pool with an enthusiastic crowd, while my favorite activities were searching through the boxes of Cracker Jacks available at the snack bar to find the prize (once it was a tiny plastic race car you had to assemble), and spending hours in the pool seeing how long I could swim underwater.

My mother on the beach in front of our beach club Peninsula House, Sea Bright, New Jersey, 1965

Years later my mother told me with a somewhat guilty look on her face that in New Jersey, she decided to keep me home from preschool to keep her company while my father spent long hours working and commuting to and from New York City. I wish she had spared herself the guilt that time, because I’m sure I was much happier at home. I didn’t like crowds, I didn’t like a lot of noise and I liked to noodle around on my own schedule investigating objects in our home, spinning fantasies in my head, and if not exactly communicating with my mother, feeling reassured by her presence. In fact, the first day she finally did drop me off at preschool, she had to come back to pick me up a few hours later. I wouldn’t use the school bathroom because I was horrified by the harsh antiseptic smell of the place, by the metal stalls, the cold tiles and even colder toilet seats, by the silence except for the sucking whirlpool of the toilets, the bitter isolation and desolation of a public bathroom. So my mother picked me up, and perhaps I never did go back to school until kindergarten; I don’t remember. But I had begun my series of lessons about myself in relation to the wide, wide world.

One of these occurred one summer afternoon, when I stepped out of the back door from the kitchen and found a girl from the neighborhood sitting on our back steps concentrating on something she held with her hands. I leaned in closer and saw that between her left index finger and thumb, she was holding the oval, brown body of a daddy long legs while with her right hand plucking out its legs one by one. In that moment I realized that people were different from one another, that it would never occur to me to do what she was doing, and I didn’t understand her motivation for doing it. I wondered if the insect was feeling excruciating pain as its legs were ripped out one by one.

In my short-lived preschool career, I traveled to the school on “the rope,” a thick yellow cord about 18 feet long with a loop held by each of about eight students on either side. A portly school monitor with a white hat with a blue band walked at the head, stopping at every crosswalk. We passed a delightful pile of maple seed whirligigs on the sidewalk; and as they were in just the right stage of dryness to throw up in the air and have them flutter to the ground like mini helicopters, I stooped to gather a handful. The school monitor barked out a command to stand up and walk straight ahead, and at that very moment began for me a lifelong dislike of rules and regimentation, because I knew in my gut that nothing was more important than the joy of tossing a handful of maple seed whirligigs into the air and watching them flutter down.

Kindergarten class; I am in the second row, middle with the white collar, Fair Haven, New Jersey, 1965

Other mysteries I pondered in those years included the feasibility of a tale told to me by a boy who lived across the street from us. He said that a family in the neighborhood had owned a baby alligator, and that when it got too big they flushed it down the toilet and it was living in the sewer somewhere below. Linden St.

I vividly remember another day when I stood in the front yard of our house with a fine light rain falling straight down onto me and into our yard. I could see that across our very narrow street, it was not raining at all in the neighbor’s yard; the rain fell only on our side of the street.

I think I previously mentioned that it brought me great joy to walk to kindergarten by myself through a little forest near our house, singing, and making up words to the songs as I walked. Sometimes I walked more and more slowly to delay the time when I would arrive in school as I found such pleasure in singing and making up my songs.

One gusty, rainy day, I was walking home on the street after school passing a house with a tiny front yard behind a wooden fence. I was holding a drawing I had made of which I was very proud. I had written underneath the drawing in the wide lines in my large kindergarten handwriting. Suddenly, a gust of wind rose up and tore the drawing out of my hand, and it blew right into the postage stamp-sized yard behind the fence. This is the part that reminds me how painful and paralyzing it was to be raised a Catholic girl in those days; perhaps it was for Catholic boys, too. I easily could have slipped under the fence in my rain boots and grabbed my drawing and continued towards home, but I stood there, tears leaking from my eyes, paralyzed with fear at the thought of scooting under a fence into a stranger’s yard (an illegal activity probably!). I stood there, staring at my drawing, just feet away, frozen in place, and knew that it was gone forever. I cried all the way home.

Me in a Sailfish on Canandaigua Lake; circa 1966

Freedom

At both sets of grandparents, there were lakes, and now, as an adult, I realize how very lucky I was to be able to swim for hours and hours, sail, be taken on long motor boat rides by my adventurous father into the middle of the lake to swim in the deep water, or on exploratory trips along the shore, seeing (in those days) rustic camper cottages, and wooded high banks barely developed. Sometimes my father took us out onto the lake on July 4th in my grandparent Bourbeau’s motorboat, and we lay down in the bow warm in our sweatshirts and covered with towels, and watched the fireworks burst overhead as the boat rocked in the wake of the other boats on the water.

In this photo I sit in an early Sailfish, or perhaps an imitation one, which my grandparents kept in their garage and launched every summer. I can tell I’m not actually sailing, as the wooden center board is sticking up, which means if I weren’t tethered to a buoy, I’d be slip-sliding all over the lake as I tried to sail. We used to sail this little boat out onto the lake on a hot summer day (I suppose our mother was checking on us occasionally from shore), capsize it by all pulling at once on the side until it tipped over, and slide down the wet angled bottom of the boat like a water slide—freedom!

My mother’s parents, T. Raymond Rice ”Grandpa Ray,” and Mary Rice, with the family cocker spaniel, Nickie; Geneva, New York

The Candy Striped Rose: The Rice Grandparents

My mother’s parents’ home in Geneva was an altogether different affair, as orderly and unhurried as the clock that chimed in the front hall every hour on the hour, dong…dong…dong. My grandfather Ray was still working when we were young, so he would glide smoothly in his pale yellow Oldsmobile from nursery warehouse to office to home, occasionally taking calls on the walkie-talkie which was installed between the two front seats of his car. His sidekick was Pedro, a solid, calm nursery worker of Puerto Rican descent, who, because my grandfather loved roses, flowering fruit trees and all sorts of plants, installed and kept up for my grandparents at their home rose beds, ornamental trees and their landscaping and lawn. As my grandfather got older and my uncle Tim took over his businesses, my grandfather spent more time at home, and had a small greenhouse installed on the mezzanine between the kitchen and the basement. There one day he showed me a new rose variety he liked and thought I would like, too, the candy striped rose. Red and white like a peppermint stick and combining candy and roses, I was enchanted.

My grandparents had very defined roles within their marriage, and didn’t improvise. My grandfather never cooked. My grandmother never learned (or cared to learn) to balance a checkbook. My grandmother’s domain was the kitchen where she produced elegant dinners (she liked to serve a salad that consisted of a half a canned pear on a bed of iceberg lettuce with a scoop of cottage cheese), and delicious sandwiches on crusty white bread for our lunches at the yacht club. And many, many cookies—sugar, molasses, chocolate chip, lemon bars...She had her rounds, the library of course, where she would collect a stack of books, and Monaco’s, one of the world’s smallest grocery stores, with a wooden floor, where nevertheless, her grocer Tom never failed to have everything she needed.

My father holds the reins of my grandfather’s Tennessee Walker “Sun Ho" at my grandfather’s farm in Stanley, NY; circa 1967

My mother and grandmother were devoted to each other in an undemonstrative way, and we stayed often at their house, and once we moved abroad in 1969, we would sometimes leave my father behind at his various jobs and stay with the Rices for the whole summer

Their house was very much an adult home, but there were just enough diversions for us children. There was a ping pong table and there were darts in the basement, and a television, and the delightful feeling of being in the secret basement world where the adults didn’t know quite what was going on. There were bikes and a paved driveway, and the yacht club where we learned to sail, and swam for hours, and ate dinner out of my grandmother’s wicker picnic basket until the sun went down.

When my grandfather finally retired, he kept a couple of horses at the farm of one of his business partners. He had a friend named Cebern Lee, a wealthy businessman whose Southern wife Muriel loved to ride and compete with her Tennessee Walking horses. The Lees had a full blown horse stable and indoor and outdoor riding rings built at their home in a rural town named Oaks Corners about six miles from Geneva, and brought from the South a, to me, exotic horse trainer named Billy with a deep Southern accent who coached Muriel on her riding, groomed and looked after her horses, and oversaw the stable and rings. Although generally mysteriously absent when we visited, I once saw Muriel from afar in an elegant black riding outfit with black ribbons at the back of her velvet helmet. Billy was tasked with teaching me and my older sister how to ride English style, with our black riding helmets and jodhpur pants. When we finally got the hang of it and could post without falling off, it was truly a delight to swing along with the rolling gait of the gentle horses Billy chose for us as they cantered around the ring.

Our grandparents Pete and Kay Bourbeau hold my older sister and me (right) on the lake side of their cottage; Canandaigua, New York; Summer 1959

Almost Paradise: The Bourbeau Grandparents

I think that because we moved so much as children (five times by the time I was seven years old), our lives tended to revolve around two more stable poles: The pole of the Bourbeau grandparents in their fascinating cottage on Canandaigua Lake, and the pole of the Rice grandparents at their elegant, peaceful and well run home in Geneva, New York.

My father’s parents Pete and Kay Bourbeau were of the era of grandparents who adored babies and children so much they could terrify us (me at least) in their physical expression of their love, pinching our cheeks so hard that it hurt, squeezing us, kissing us and (my grandmother) dressing us like dolls. It is hard to imagine them anywhere else than in their tidy little cottage world, my grandfather in his ancient dull green Bermuda shorts held up by an old leather belt across the rotund torso about where his waist would have been, his oiled, slicked back hair, his ankle socks and flat sneakers with laces he wore all day and into the water to walk on the rocks in the lake. His domain was the garage at the back of the house (away from the lake), where a high wooden work table lined one wall, with dozens of small drawers holding nuts and bolts and fasteners and tools of all kinds. He rarely if ever went to the hardware store, and he could fix just about anything. On the posts of the garage were nails that held his hat collection from all over, a helicopter beanie, a New Year’s Eve party hat, a straw campesino hat (the kind made for tourists) from their yearly drive to Acapulco. I think he only smoked his cigar a short while in the evening, but he smelled of cigar all day long, and of hair oil, and old man, and fresh lake water as he swam every day in the warm weather.

When we visited them on Sundays, the Sunday paper had already arrived with the color comics section. My grandfather would find a piece of blank paper in the many compartments of his upright desk, he would pull out his pocket knife and whittle down his stubby pencil to a fine point, would lick the tip, would draw a few little circles in the air to warm up, and would finally draw us a perfect version of Blondie and Dagwood, with Dagwood's weird black oval eyes and tufts of hair sticking out the sides of his head.

On the enclosed sleeping porch facing the lake, there was a crude but decorative wooden armoire from Mexico that held our favorite treasures. There was a ukulele, more silly Mexican straw hats to be worn while playing the ukulele, a wooden snake that wiggled, a round poker chip storage caddy, and our favorite, the hand-cranked playing card shuffler. There was also a blue Maxwell House coffee can filled with crayons, and coloring books.

My mother in Canandaigua Lake with (left to right) my sister Jane in a duck floatie, my older sister and me; circa 1964

My grandmother Kay’s domain was the kitchen, where she produced the crusty, buttery grilled cheese sandwiches topped with strawberry jam we adored, and performed the daily feat of scrubbing down the copper bottoms of her Paul Revere pans until the copper shone and they looked brand new. It was this same determined energy she brought to the task of washing our hair; she laid a towel over the edge of the bathroom sink, squirted on the shampoo, and painfully massaged our poor scalps with her pointed, shellacked, hard-as-diamonds fingernails as we just winced and waited for it to be over. I think she believed that it was good for the circulation. She also hewed to that often-heard belief that brushing your hair 100 times every night would make it beautiful.

At 5:01 or 5:02 pm in the Bourbeau grandparents’ household, it was time to crack open the kitchen cabinet containing all the liquor for ‘cocktail hour.’ The chief attraction of this for us children was Grandpa Pete’s little red plastic pail that contained his extensive and fabulous collection of brightly colored cocktail stirrers; some had Hawaiian hula girls on one end, or flamingos, giraffes, lobsters and all sorts of marine animals, words, hearts, and names of bars and restaurants.

As cocktail hour progressed, the cottage would fill with the delectable smell of pot roast, roasted potatoes, or lamb. The grandfather who sang silly songs with the ukulele and drew Sunday comics characters would metamorphose slowly into the man who argued with and berated my grandmother, taking offense at her every word, his voice getting louder and louder and his tone more aggressive. I seem to remember my father trying to calm him down; it was as if they were all caught in a web no one could name or understand.

When the after-dinner coffee was served to the adults, it was time for the ritual dropping of the saccharin tablets. No one in that house took coffee with cream and sugar; I’m not sure why. The white saccharin tablets lived in a tiny porcelain bowl with a cunning little spoon at the center of the table. Each grandchild had the enviable task of standing on a dining room chair, holding the saccharin tablet as high as she dared and dropping it into one of the adult's coffee cups. This job we performed with such care and pride that we seldom missed.

After dinner it was time for the Ed Sullivan show. which we children generally watched from under the dining room table, and then it was time for “vitamins” (M&Ms in a red enamel bowl) and then bed. In the summer we tucked ourselves into the day beds on the sun porch and fell asleep with the lake breeze coming in through the screened windows, and to the sound of crickets and the lake lapping against the shore.

Me at six, my sister Jane, and my older sister, in our Easter outfits, at our Bourbeau grandparents' cottage in Canandaigua, New York; 1965

Easter Sunday

I’m not sure who was providing the matching outfits, probably my father’s mother Grandma Kay (she of the many names) or possibly my mother with financial assistance from her family. I appear to quite like my blue coat with brass buttons, my Easter hat, and my red purse, which would have contained my white gloves to be worn in church (why, I do not know), an embroidered handkerchief, and possibly a black superball, slinky or a lime-green plastic rat fink figurine, which was then my favorite toy. When in school, the rat fink lived in a small cardboard jewelry box lined with folded Kleenex so he could rest comfortably. It was very reassuring to lift my desk lid every so slightly and see him there.

A little later in life, I disliked any occasion that required special clothes, but here my sisters and I seem to enjoy the occasion and the appreciative gaze of the adults.

Sneaking in a toy to take to church was, as I recall, absolutely essential. Otherwise, the only relief from the excruciating boredom of the long service was staring at the back of people’s heads in the row in front, right at the intimate nape of their necks, a place they had never and would never see for themselves I liked to reflect. Or else clicking over and over the little brass clasp that held your hat or your gloves, or bothering one’s sister. Or perhaps reading a hymn, or the church newsletter, but that was even more boring than just sitting there bored.

Before we entered the church, my mother would don a black or white mantilla, which was a long piece of lace that covered the head and dropped to the shoulders. Women weren’t allowed to enter a Catholic church without a head covering; I don’t recall her ever wearing a hat. I do remember looking at my mother in church as she followed the mass and thinking, what is going on inside her head? What are we doing here? She did it, so we did it; we didn’t ask questions. On Sundays when we were quite young, and on Easter and Christmas, my father went to church as well. Then later he thought of things he needed to do, like fix the lawn mower, or water the grass.

As I got older, I listened more to what the priest was saying, and tried to reason things out. Did Jesus really rise from the dead after three days? And if that is possible, why do such things not happen now? And I do remember one question I was troubled by when I got older, about eight years old: Jesus suffered, sure, nails through the hand, drying up and dying up there for all to spit on and see, so that we humans could have ‘eternal life.’ But, I noticed, plenty of humans were suffering down here below, perhaps suffering even more than Jesus did, in warfare, Jews in concentration camps, Japanese children burned and disfigured by atomic bombs--all sorts of brutality and suffering. I knew some nuns who were intelligent and even kind, but I never would have dared to speak my concerns aloud to them or in Sunday school, or to any adults I knew.

My mother, me, my father, and my older sister in the driveway of my mother’s family home (their house is to the right, not seen in this picture) in Geneva, New York; 1959

Bitter Arguments

My mother broke off her engagement to my father when he was in Japan, but after he returned, it was on again, and they were married in December 1956. Here is the young family, on a visit back East from Kansas City, standing in the driveway of the house where my mother grew up, and where her parents still lived. My mother’s brother and sister lived a few miles away. My father’s parents lived about 20 miles away in a winterized cottage on Canandaigua Lake, the next lake over from Seneca Lake where my mother’s hometown of Geneva was located. As much as my parents wished to strike out and be independent, with their own home and new friends in Kansas City, the pull for them to return to all their family in the Finger Lakes must have been very strong. I’m not sure exactly how events unfolded and in what order, but I do know that my parents were soon to make two very bad decisions.

To step back a generation…my mother’s father T. Raymond Rice made the painful decision to drop out of Georgetown University his junior year to come home to Geneva to help salvage his father’s nursery business. Geneva was a nursery industry town with fields of flowering fruit trees and warehouses of flowers and roses to be shipped out all over the Northeast. My great-grandfather was on the board of a bank, and took the fall for another board member who embezzled money from the bank and left town. In those days, board members were personally liable, and the impact on my great-grandfather’s personal finances and business was huge. My grandfather’s plan all along had been to follow his father into the nursery business, but he regretted his lost years at Georgetown probably for the rest of his life.

My grandfather became a tough and driven businessman who eventually built his own successful nursery and a dry cleaning business as well. My father, also driven, strong-willed and opinionated, decided to accept his father-in-law's offer of a managerial job at his dry cleaning business in my mother’s hometown. Only in retrospect could the various parties see what a very, very bad idea it was for my independent father to work under his exacting and somewhat domineering father-in-law.

When they moved back East so my father could start this new job, my parents couldn’t find a house to rent in town, so they rented an unwinterized cottage on the east side of Seneca Lake. There my second sister Jane was born; I remember the night she came home from the hospital with my mother, and the only other thing I remember was COLD!! My parents made up for this later in life by finding us some lovely houses in other places we lived.

It wasn’t long before my grandfather and father butted heads and my father quit, or was fired (I’ve heard both versions) and that experiment was over. We moved to a humble little house in nearby Rochester, New York, where my father took a shot at running some laundromats. I can imagine his struggle and confusion. One night, my older sister and I heard my parents arguing bitterly after we were already in bed. We heard my father say, “I’ll get my suitcase and pack," and in my memory we looked at each other in terror, and on my sister’s face, just five or so then, besides the scared look, there was also a thoughtful look, as if she were already calculating, “how is this going to affect us, and what do we do next?'

My mother Mary Ann Rice with her boyfriend Beezy on the night of her senior ball; Geneva, New York; circa 1951

Life is a Bowl of Cherries

And the two little girls below wouldn’t have existed without this young woman, my mother Mary Ann Rice, seen here on the evening of her senior ball with her high school boyfriend “Beezy.” She looks so happy and content here; I don’t think I ever saw her with quite this mild, content look on her face. She used to say, “I thought life was a bowl of cherries until I was 40 years old.” I’m not sure exactly what happened to change her mind.

She was very, very intelligent, competitive I'd say, driven to excel. Her grades and understanding were so good, she skipped third grade at her Catholic school St. Stephens. Most of her classmates continued on to the Catholic high school DeSales. But my grandfather insisted that she should go to the public school, Geneva High, where she would have a greater choice of academic opportunities and activities. She acquired a much larger pool of friends, got involved in debate and numerous clubs, and was always at the top of her class. In her senior year, she won a trophy for Best Girl Athlete.

Her boyfriend Beezy was an orphan who lived with his aunt and uncle a few blocks away. My mother’s parents were fond of him, he was often at their house, and was allowed to drive the family car. I once somewhat cruelly asked my mother, after seeing this photo in her album, why she hadn’t married Beezy instead of my father. Beezy was a few years younger than my mother, and their relationship ended when she went to college,

My father (second from right, with a cigar) with Marine buddies in Japan, circa 1953

Reveille

After college, my father joined the Marine Corps, was commissioned as a first lieutenant, and shipped out to Japan in a Marine expeditionary force in 1953. When we were kids, we were fascinated by the color photos he had taken of Japanese sumo wrestling, the wrestlers with their immense pale fleshy bulk, stoic expressions, loincloths, and jet-black, oiled hair in topknots, sitting at the corners of the ceremonial rings.

He told a story that seemed a bit too mythical to be absolutely true that he was standing in a line of Marines stateside and an officer was counting off men to join the Korean war, and cut off the count right as my father got to the beginning of the line. So he just missed becoming one of the 30,000 Marines who died in the Korean War, 30,000 men who never had families or first homes or jobs, Perhaps that is why he looks so jubilant here—he is celebrating life. I’m sure he was energized by the curvaceous cocktail hostess, prostitute or whatever she was just inches away—not a profile he had encountered growing up in New England.. He was stationed at Atsugi Air Base in Japan from 1954 to 1956.

When we were kids and had a weekend outing planned, he woke us up by coming into our rooms, making his hands into a bugle horn with this thumb the mouthpiece and hum-buzzing “Reveille” at the top of his lungs. “You’ve got to get up, you’ve got to get up, you’ve got to get up in the MORN-ing!!”

My father Dick Bourbeau at 18 or so, circa 1949

My Father, Poised for Adventure

Before the two adorable, mesmerized little girls below existed, there was this boy, my father Richard Lee Bourbeau, usually called Dick. His fleshy cheeks and the ‘widow’s peak’ of his hair on his forehead make him look young, but I am guessing this is a portrait paid for by his parents before he went off to prep school at Berkshire School in Massachusetts (his family lived in West Hartford, Connecticut), or possibly his senior photo before he went off to college.

His dreams and desires I can imagine: to strike out on his own, get away from his bickering parents. to conquer new worlds, to have sex, to see more of the world, to have adventures. His father was a salesman for Shuron Optical, an eyeglasses manufacturer. His mother’s father was the president of Colt firearms manufacturing in West Hatford. According to my father, his grandfather was a “piece of work,” which scared me because my father and his father were themselves “pieces of work,” so I couldn’t imagine how much more domineering, bullying and loud his Colt grandfather must have been. Plus I could see that his daughter—my father’s mother—was brittle, cowed, damaged in some way. My father was allowed to drive his grandfather’s horse and buggy to get back and forth to his own home and his grandfather’s large house—he loved that. His parents had a bit of a farm with chickens and a couple of horses—he loved that too.

My father’s mother, known as Kay, used to make us laugh with delight when she recited her whole name (which included her baptism, communion, confirmation name, her maiden and married names and others; I can only remember some of them: Katherine Dolores Aloysius something something Aveline Conner Bourbeau. Although I could sense her hidden wounds, my grandmother also at times could seem tough as nails. She joined the Women’s Army Corps during World War II. During that time, my father was taken care of by a sort of nanny, on the young side I think, and he adored her. He was telling me about this in his nursing home when he was in his 80s with dementia. When he mentioned that his mother came home from the WACs, and his nanny abruptly disappeared, he started weeping. He must have been holding in that feeling for a long, long time.

My older sister and I watch cartoons on a black and white television; Kansas City; 1960

Television

There is something very different about this photograph than other photos of my childhood. It is another photo of my sister and me, but there is some other very powerful object in the room we can’t see; it commands my sister’s and my complete attention. We don’t even notice the human being who is also there, quite close, taking this photo.

We were one of the early generations of American children to grow up with an object in our houses that took possession of our consciousnesses for hours at a time, As we watched the black and white flickering of the television set, we became oblivious to everything else around us. On Saturday mornings, we raced downstairs the moment we were awake to watch Saturday morning cartoons. Here my sister and I watch a black and white cartoon, probably “Popeye the Sailor” or possibly “The Flintstones,” but we do not look in the least entertained or amused; instead we look deeply concerned as if we were watching a news program on the Vietnam war, or a report on Soviet missiles in Cuba. Who can say looking at this photograph and the expressions on our faces that television is a light, diverting experience?

Americans had so much less stuff in those days; there are no books on the coffee table, no coasters, no vases, no knickknacks. There are no throw pillows on the couch. I vividly remember the world like this, with much less stuff in it—a bit stark I suppose, but less to clean, less to think about, less to distract. People didn’t shop for recreation then. There were no malls. Mainly I remember specialized stores that sold what you needed. There was the bakery for bread, the small department store for any kind of clothes you might need, the appliance store for washing machines and vacuum cleaners, The Zenith store for televisions and radios, and in some towns stationery stores with pads and envelopes, books and greeting cards.

In such a world, one got to know objects more intimately; I remember the exact fabric and feel of the couch in this picture, and the shiny surface and contours of that coffee table. I remember on the day of the John F. Kennedy assassination in 1963 playing for hours and hours with a colorful plastic ball that had somehow become deflated, I shaped it and squeezed it and molded it into a bowl exploring its pliability as the adults murmured and sometimes cried in the background.

My father with my older sister; my mother holds me; Kansas City, Missouri; Christmas 1959

Father and Mother United?

How radiant my parents look here with health and youth and youthful optimism! I feel both admiration for them and deep sadness, because what you see here is true, but it is also a passing illusion, one that I don’t think lasted very long. They are in their early 20s, my father a few years older than my mother, and at this point, I imagine they shared the same goals, the same vision, with variations, of creating a small family, with at least one boy child, of course, living in a spacious house with like-minded neighbors, impressing their parents and siblings back East with their independence and sophistication.

They both were athletic—my father played football and was on the ski patrol at Middlebury College; my mother taught swimming to girl scouts. They both were very bright, my mother in an intellectual, bookish way (she knew an astonishing amount of American and European history), my father in a worldly way—he thought and knew a great deal about the way the world worked, how the parts interconnected, things I’m sure my mother would never notice. We traveled a lot when I was a young teen, and he would always notice what cargo was being unloaded from ships, what a truck was carrying. He noticed if the people of a town were very poor, people’s ingenuity at rigging up a water system or their clever schemes at making money from tourists.

My parents interests diverged dramatically in (at least) one area: My mother was happiest with a stack of biographies or history books and time to read over the weekend. My father was always chasing the next party or gathering, and saw no use for books at all. At all. “Your mother would rather stay at home and read about it,” he’d say. He was more than dismayed, he was outraged even, when I requested a $35 copy of the The Riverside Shakespeare as a high school graduation present. I’m not sure how he made it through prep school and college.

Knowing what came later, it seems to me that much is revealed in this photo about our family dynamics; it is predictive of what was to come. My parents aren’t interacting or touching each other, they sit apart. My father holds my sister, 18 months older than me, and my mother holds me, tenderly, protectively but perhaps too possessively, perhaps clutching a little. I came to feel later that my parents created two families, my father bonded with my older sister as his favorite child, and my mother bonded with me. I don’t think you’re supposed to do it that way, but perhaps no one told them. They were in the Midwest far from their families.

In my stroller in Kansas City, Missouri; May 1960

A Pigeon-Toed Angel

I’d like to think that this photograph shows the essential me, eager, curious and ready to be delighted. My father was the official family photographer, but the trusting look on my face in this picture makes me think It was my mother who was taking the photograph on this sunny May day. I am wearing a smocked dress, which I believe was a fairly standard look for girl babies in those days. The puffed sleeves and short dress that flares out make me look like a little angel, or one of the discreetly clothed Midwestern putti with wings just beginning to sprout from the shoulders.

My father had taken a job with a company called Recordak, and had gone to Kansas City, Missouri before us to purchase his first house for $10,000, with help from his parents. For Recordak, a subsidiary of Eastman Kodak, the photography company, he sold microfilm and early microfilm machines to libraries and banks to store their records. He told a story of going to the Harry Truman library and seeing Harry Truman himself pacing across the lawn.

I have just a few impressions and memories from that time. My first memory is of seeing my mother sitting in a chair, it seems to be a rocking chair, sewing a tuft of feathers on the hat my father wore to work. It was the type of fedora hat that businessmen wore in the 1950s and ‘60s, and I suppose some of them had a touch of Tyrolean style, a touch of colored feathers. Something tells me that if my mother were alive today, she would tell me this could not be true, but that is what I see in my mind’s eye, my first conscious memory of this world.

I have a memory too of a pale green tricycle and the concrete patio in our backyard. And just two more memories from this time, both having to do with feet. My sister and I, at ages about three and one and a half, wore one-piece pajamas with feet in them. We had a wooden stool to step up to the sink where we brushed our teeth. I tripped on the floppy cloth of the pajama feet, and I fell and cut my chin. It was a shock how quickly the world could trip one up and deliver pain. It was a minor injury but to this day I have a neurotic and frequent fear of tripping on things; I move shoes so they won’t be in the way, I shove chairs back so no one will trip on them getting up in the night, I push drawers in, I straighten rugs..

My mother believed the doctor who told her my feet turned inward and I would grow up to be permanently “pigeon toed,” And so, at one year old, still in my crib, I was made to wear at night a special pair of white leather shoes that reached to my ankles and were fastened to a flat steel bar that held my feet straight and wide apart. What agony it must have been to wear those steel-locked boots at night, my feet prisoners, not able to turn, kick or stretch. My body carried a memory of my bound feet well into my 30s, until at some point, I consciously remembered the bound shoes and finally the sensation faded and my feet were free again. That was just the first time the little angel was corrected and remediated. There were years of braces to straighten my teeth. There were lessons after school with a strange woman who whose job was to teach me how to swallow without pushing my tongue against my teeth so I wouldn’t have an overbite, And there were lessons at school because I couldn’t say my Rs and Ws correctly; I said “wed ragon” instead of “red wagon.” There were many corrections, corrections in how you sat, how you crossed your legs, and what you did at the dinner table. (Never ever put your elbows on the table. Why? I still would very much like to know.) And corrections to the heart and mind and soul in the confessional at the church.